- Visibility 64 Views

- Downloads 28 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.008

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma

Case

A 4-week-old male was referred to the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Ophthalmology Department for review of a fleshy lesion on the lateral aspect of his left eye. The lesion was noted shortly after birth, and initially thought to be related to birth trauma from forceps delivery. He had no significant medical or family history.

Initial clinical examination of the left eye revealed a cloudy cornea with a lesion extending from the limbus into the anterior chamber. Intraocular pressure was 12mmHg in the left eye. Mild opacity of the anterior lens was noted, and there was no view to the fundus. The right eye appeared normal. Diagnostic imaging and examination under anaesthesia was arranged.

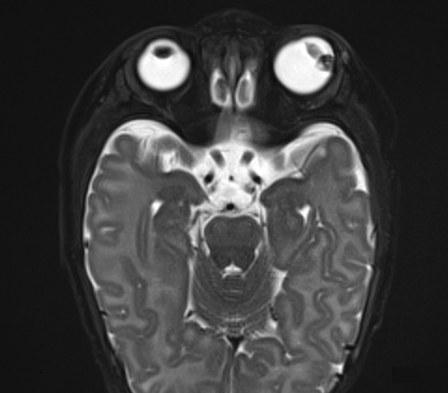

Ultrasound biomicroscopy identified a 11.6x6.2x5.7mm ciliary body lesion, with intra-lesional cystic spaces and hyper-echoic foci, but absent posterior acoustic shadowing. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed an irregular intraocular lesion arising from the ciliary body, extending into the anterior and posterior chambers. It was hypointense on T1- and T2-weighted images ([Figure 1], [Figure 2]).

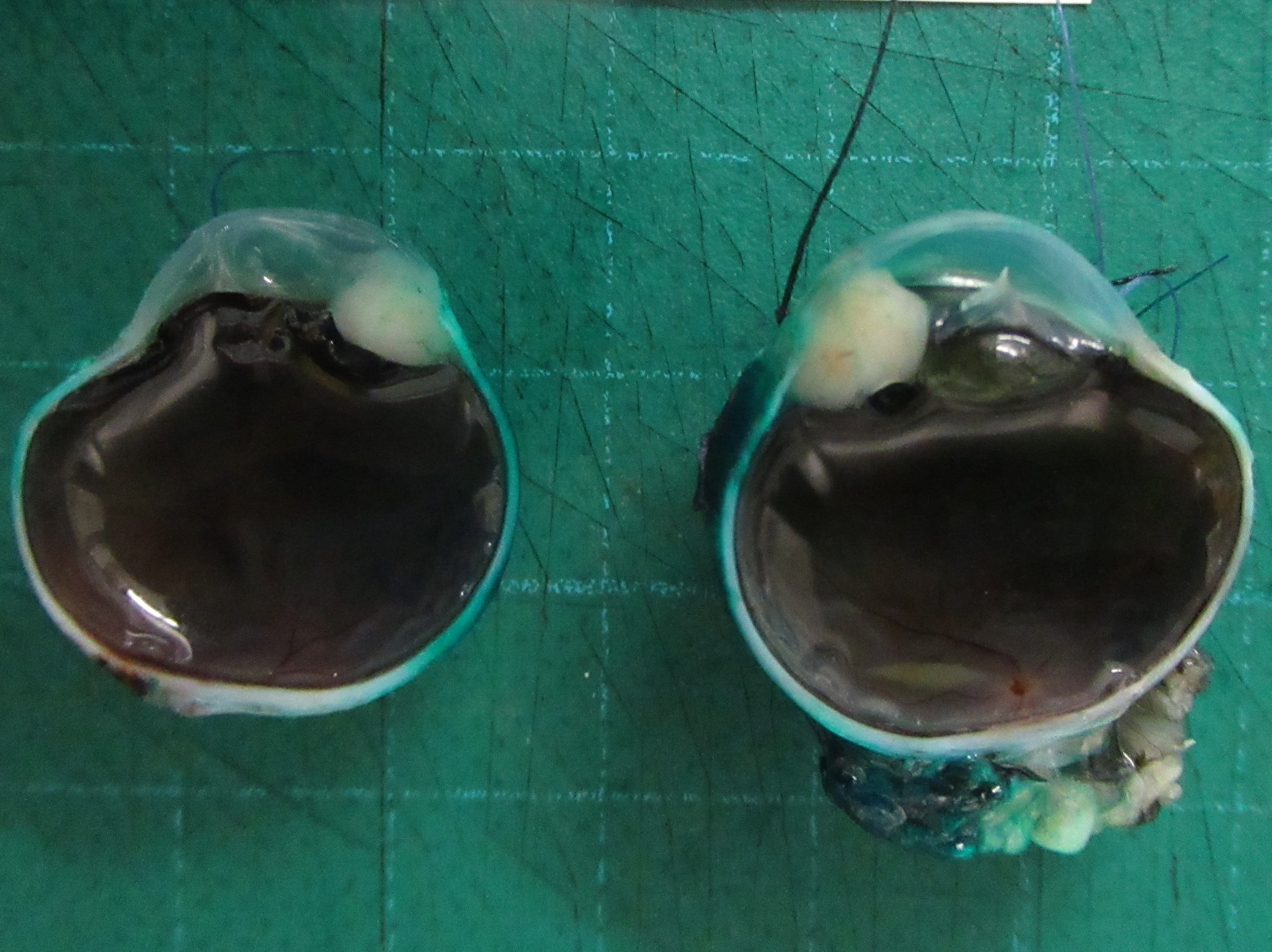

EUA occurred 11 days later, at which time the intraocular pressure had increased to 40 mmHg (compared to 13mmHg in the right eye) and the eye was buphthalmic (horizontal corneal diameter 13mm compared to 11.5mm in the right eye). A highly vascular, pink fleshy lesion arising from the ciliary body was noted, extending to the inner surface of the cornea ([Figure 3]). The anterior chamber was filled with fibrinous exudate, the pupil was irregular with synechiae adhering the iris to the lesion. Fundus examination was largely obscured by the lesion, but the visible retina appeared flat.

The differential diagnoses included malignancy (e.g. medulloepithelioma or an atypical retinoblastoma) or an inflammatory lesion (e.g juvenile xanthogranuloma). A biopsy was not performed due to high risk of bleeding and the potential for seeding malignant cells. The patient underwent left enucleation given the limited visual potential of the eye and concern for malignancy.

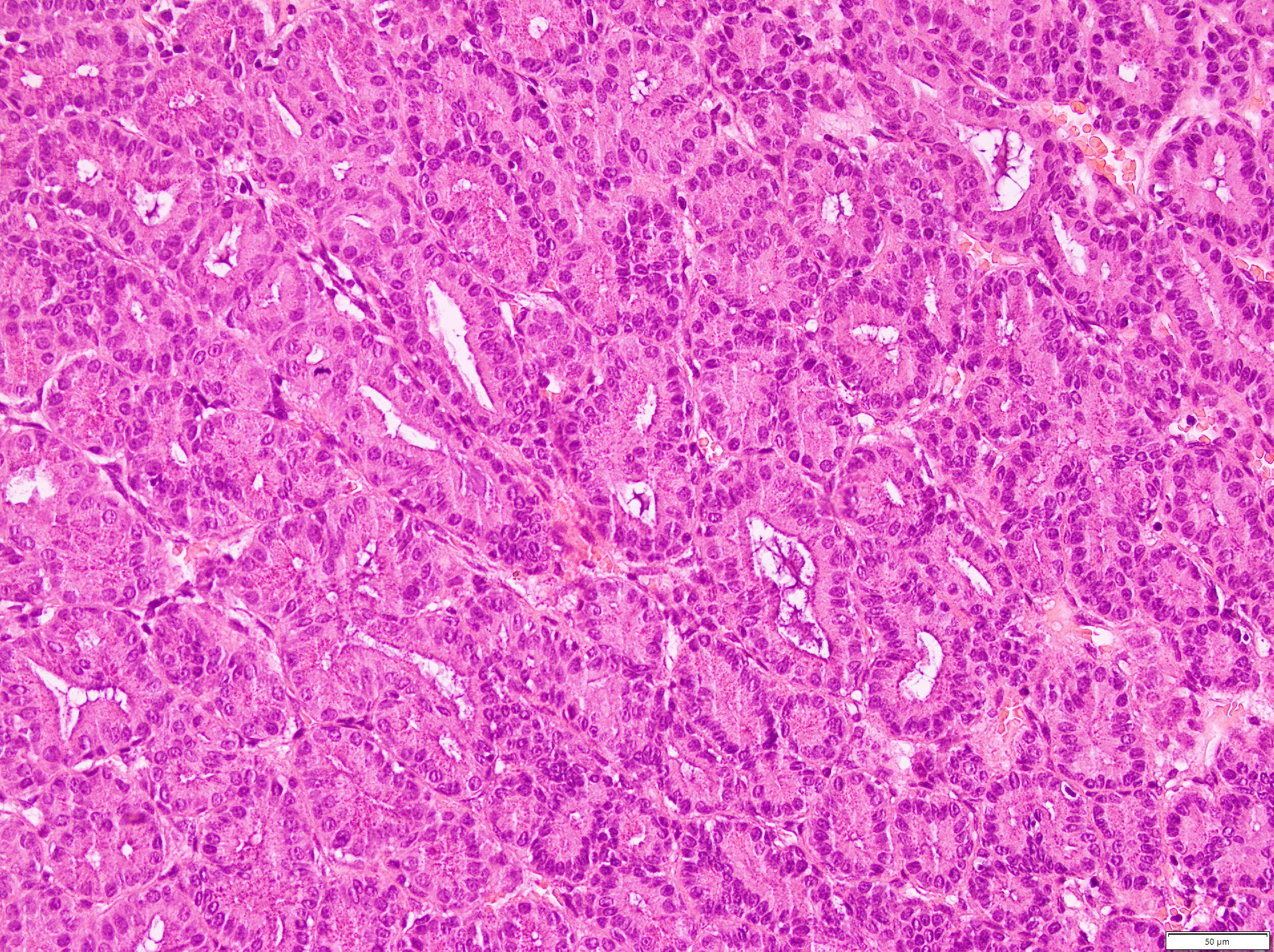

Histopathology confirmed a tumour arising from the ciliary body, consisting of acini lined by cuboidal cells with basally-located round nuclei positive for AE1/AE3, CK7, CD99 and patchy staining for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) ([Figure 4], [Figure 5] ). The cytoplasm contained granules positive on staining for Perioidic acid Schiff (PAS) and diastase resistance. The cells were negative for synaptophysin, S100, GFAP and LIN28. These findings were consistent with intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma.

At 6-month follow-up and repeat prosthetic eye fitting, the socket was well-healed with no sign of recurrence.

Discussion

Lacrimal gland choristomas are rare, especially intraocularly. An intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma (ILGC) was first reported by Puech in 1887, and there have been fewer than 20 cases reported since.[1] Previous aetiological theories include aberrant cell differentiation or migration of cells during embryogenesis, intraocular extension of lacrimal tissue along pre-existing scleral defects or localised abnormal expression of signalling molecules associated with lacrimal gland morphogenesis.[2], [3] Most ILGC arise from the iris or ciliary body, and may extend to the limbus or sclera.

ILGC typically affect young children, with individuals presenting at a median age of 7 months old (range 2 weeks old - 6 years old). The most common presentation is an abnormal-looking eye, and some may present with associated orbital cellulitis. Clinical features include a fleshy, vascular mass, which may be accompanied by vision-threatening secondary complications such as glaucoma, cataract, or retinal detachment. Visual loss associated with choristoma may also relate to intraocular tear fluid production i.e. the electrolytes, proteins, metabolites, lipids and mucins within tear fluid may contribute to inflammation or increase intraocular pressure. [4]

Radiological findings are not consistently reported throughout the literature. Ultrasound usually reveals an echogenic mass, often with a cystic component. Jung et al described MRI characteristics, reporting low and high signal intensity peripherally on T1- and T2-weighted imaging, respectively. [5]

Lacrimal gland choristoma share identical histopathological features and immunohistochemical markers (including AE1/AE3, CK7, EMA, CAM5.2.) to normal lacrimal glands. [5]

The differential diagnosis of ILGC includes medulloepithelioma, juvenile xanthogranuloma, retinoblastoma, naevus or melanoma. For our patient reported herein, medulloepithelioma was the primary differential diagnosis prior to treatment. The similarities between medulloepithelioma and ILGC presents a challenge in clinical diagnosis; both present as an in irregular greyish white to pink, vascular lesion often with a cystic component. Additionally, both medulloepithelioma and ILGC may involve the ciliary body and iris. The median age of diagnosis from the few reported cases of ILGC is 7 months compared to 5 years old for medulloepithelioma. [6] However, medulloepithelioma has been reported in children as young as 6 months old. Both disease entities may be associated with secondary complications such as cataract and glaucoma. On MRI, medulloepithelioma are isointense to mildly hyperintense to vitreous on T1 weighted imaging; our case demonstrated a hypointense lesion on T1 weighted imaging. [7] This was also found in the only other case in the literature reporting MRI findings. [5] Further cases would be required to validate this association.

Although previous studies have successfully managed ILGC conservatively following biopsy or with local resection, enucleation is warranted in cases of blind, painful eyes secondary to complications. In our case, enucleation was performed on suspicion of malignancy as well as secondary glaucoma associated with pain and poor visual prognosis. Of note, three cases in the literature, reported separately, were initially managed with local resection that later proceeded to enucleation following recurrence and secondary complications. [8], [9], [10]

Conclusion

ILGC are benign lesions affecting young children that may be difficult to distinguish from other conditions such as medulloepithelioma. While they are often treated successfully by conservative measures, secondary complications or recurrence may necessitate enucleation.

Source of Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- P Puech. Adenome de la choroide. J Med Bordeux Sud-Ouest 1887. [Google Scholar]

- D Ranganathan, P Lenhart, G B Hubbard, H Grossniklaus. Lacrimal gland choristoma in a preterm infant, presenting with spontaneous hyphema and increased intraocular pressure. J Perinatol 2010. [Google Scholar]

- V Govindarajan, M Ito, HP Makarenkova, RA Lang, PA Overbeek. Endogenous and ectopic gland induction by FGF-10. Dev Biol 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AAV Cruz, RM Limongi, ED Feijo, TJ Enz. Lacrimal gland choristomas. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2021. [Google Scholar]

- JY Jung, JH Kim, ST Kim, HJ Kim, YC Weon. MR features of intraocular ectopic lacrimal tissue. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WL Broughton, LE Zimmerman. A clinicopathologic study of 56 cases of intraocular medulloepitheliomas. Am J Ophthalmol 1978. [Google Scholar]

- RK Sansgiri, M Wilson, MB Mccarville, KJ Helton. Imaging features of medulloepithelioma: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol 2013. [Google Scholar]

- A Tauziede-Espariat, O Roche, J L Dufier, M Putterman. Recurrent lacrimal gland choristoma of the ciliary body in an infant mimicking a medulloepithelioma. Eur J Ophthalmol 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Dallachy. Ectopic Lacrimal Glandular Tissue within the Eyeball. Br J Ophthalmol 1961. [Google Scholar]

- WR Green, LE Zimmerman. Report of eight cases with orbital involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 1967. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

Rolfe O, Staffieri S, Matthew A, Elder J, McKenzie J, D’Arcy C, O’Day R. Intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma [Internet]. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 08];10(1):40-43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.008

APA

Rolfe, O., Staffieri, S., Matthew, A., Elder, J., McKenzie, J., D’Arcy, C., O’Day, R. (2025). Intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, 10(1), 40-43. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.008

MLA

Rolfe, Olivia, Staffieri, Sandra, Matthew, Anu, Elder, James, McKenzie, John, D’Arcy, Colleen, O’Day, Roderick. "Intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, vol. 10, no. 1, 2025, pp. 40-43. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.008

Chicago

Rolfe, O., Staffieri, S., Matthew, A., Elder, J., McKenzie, J., D’Arcy, C., O’Day, R.. "Intraocular lacrimal gland choristoma." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty 10, no. 1 (2025): 40-43. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2024.008