- Visibility 247 Views

- Downloads 64 Downloads

- Permissions

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijooo.2021.018

-

CrossMark

- Citation

A study on use of adjuvant therapy of steroid and antibiotics in treatment of unilateral retinitis following typhoid fever in a medical college in Kuppam

- Author Details:

-

Shiva Sagar N *

-

Ananthanag E

-

Usha Kiran R

-

Narayan M

Abstract

Purpose: To compare the efficacy of adjuvant therapy of topical steroids eye drops with oral antibiotics and monotherapy of oral antibiotics in a typhoid fever associated retinitis.

Materials and Methods: The study was conducted on a 30yr old male who presented to our OPD with decreased vision in left eye and was followed up for 1 month.

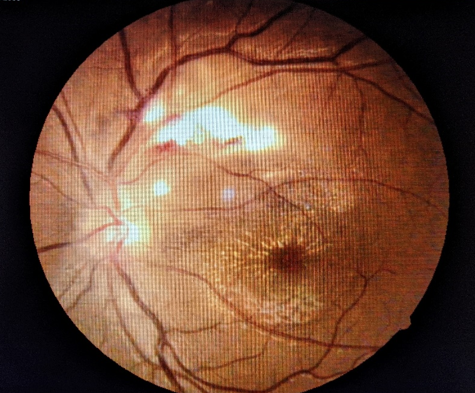

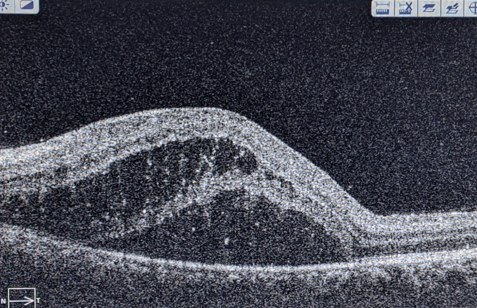

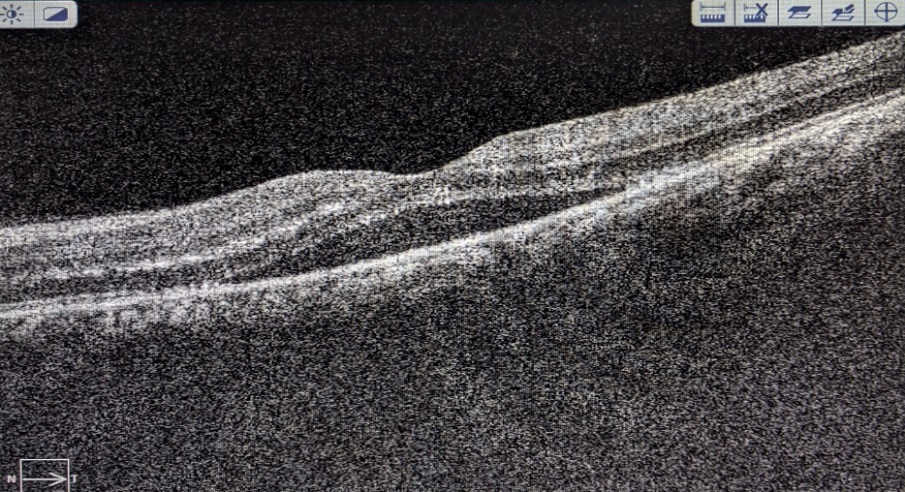

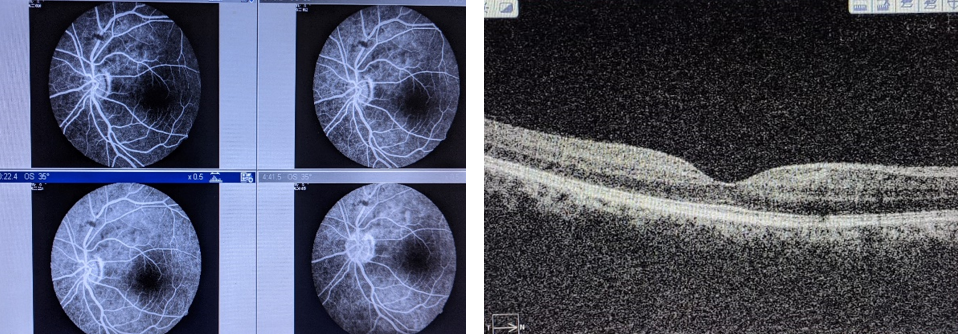

Results: A 30yr old male patient presented to our OPD with decreased vision with left eye with history of typhoid fever for a duration of 4 weeks and was treated successfully. His BCVA was 6/6 in Right Eye and 6/36 in Left Eye. Fundus examination revealed multiple whitish ill defined lesions suggestive of retinitis lesions which was noted superiorly to the disc which was associated with macular neuro-sensory detachment and blurring of disc margins in the left eye. Significant improvement in BCVA was observed with adjuvant therapy of topical steroids with antibiotics over a period of 1 month. Diagnosis of post typhoid immune mediated retinitis was made with good resolution following treatment.

Introduction

Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella typhi. It leads to enteric fever, septicemia and gastroenteritis. Salmonella can rarely affect the eye either by direct infection or rarely by immune-mediated mechanism. Hersing and Duke-Elders[1] reported typhoid-related uveal complications including iritis, retinal hemorrhage, choroiditis, endophthalmitis and panophthalmitis.

Typhoid fever affecting the eye has been reported as early as 1893 [2] Practically every layer of the eye can be affected. The role of typhoid fever in causing immune mediated retinitis has recently spiked interest in the ophthalmology community. The clinical features are similar to the other PFR sequelae described in patients who are immunocompetent and have had fever prior to the onset of ocular symptoms. Typhoid fever and its ocular manifestations can be described during acute stages of the disease or post-fever stages. During acute stages the patient can present with catarrhal conjunctivitis, ulcerative keratitis, keratomalacia, iridocyclitis, choroiditis, vitritis and optic neuritis and optic atrophy paresis of accommodation ptosis and abducens nerve palsy. Post-fever ocular signs described include focal or multifocal retinitis, with or without stellate maculopathy, vasculitis and, retinal venous occlusion due to vasculitis resulting in intraretinal haemorrhages's, cotton wool spots and retinal and optic nerve head edema, neuroretinitis, large neurosensory detachment, retinal detachment, frosted branch angiitis, pseudoretinitis pigmentosa, endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, orbital cellulitis and tendonitis.[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] OCT may show hyperreflectivity in the inner retinal layers corresponding to the area of retinitis.

Diagnostic tests Blood culture isolation of S typhi is the diagnostic method of choice in typhoid fever. Incidence of positive isolates varies enormously[8] However in a series from India 527 (9.2%) isolates were obtained from 5,735 suspected cases.[9] Blood culture identifies 45-70% of confirmed cases, even with the availability of newer continuous automated culture systems.[10], [11] Serological tests including the WIDAL test are widely available in endemic settings, although in the absence of paired clinical samples or background population sero surveillance data these tests perform poorly with low sensitivity and specificity.[12] WIDAL test determines “O” and “H” antigens of S. typhi and “AH” and “BH” antigens of S. paratyphi. It is usually the third week after the onset of typhoid fever complications may set in and it is usually referred to as the week of complications.[1] The sensitivity of S. typhi detection from blood can be increased by using ox-bile as a selective culture media. Ox-bile reduces both coagulation and serum complement killing activity and causes the selective lysis of human rather than Salmonella cells.[13], [14], [15], [16] A faster culture-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assay incorporating a brief preincubation in ox-bile along with PCR amplification of the S. typhi flagellin gene, fliC has been described.[17], [18] In a study by Darton et al. culture-PCR assay performed well, identifying extra typhoid cases compared with routine blood culture alone.[19] A study done to compare PCR with blood culture, typhi-dot and Widal test for the diagnosis of typhoid in patients taking antibiotics showed positivity rate of PCR was significantly higher as compared to blood culture, Typhi-dot or Widal test for diagnosing typhoid in patients who were already taking antibiotics. This is useful in cases of post-fever immune mediated ophthalmic sequelae. [20] In a study by Redhuan et al.[21] they found a higher sensitivity for IgA compared to either IgG/IgM antibodies in saliva, but for serum, IgG had a higher degree of sensitivity compared to IgA and IgM. Salivary IgA anti-50kDa antibody can be a potential biomarker for routine screening, whereas serum IgG is more suitable for confirmatory test due to its higher specificity in typhoid cases. In a study by Acharya et al.[22] they found high Widal titres were associated bilateral involvement, extensive lesions defined as disc involvement, retinitis, vasculitis and macular involvement and poor visual acuity which was found to be statistically significant. Pathogenesis Typhoid retinitis may occur secondary to direct invasion of the S. typhi bacilli or immune mediated reaction attributed to post infectious immunologic effects which may lead to an immune response that reacts to self-antigens (for example, heat shock protein and myelin basic protein) or homology between retinal proteins and microbial peptides (similarity between S-antigen and microbial peptides such as yeasts, Escherichia coli, and hepatitis B virus) or molecular mimicry leading to autoimmunity (S antigen and interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein-IRBP).[23] Endogenous endophthalmitis and panophthalmitis has been described post enteric fever which may be an example of direct invasion of the bacilli even though the ocular onset was reported 6 weeks to 3 months later. S typhi tropism towards endothelial cells may cause vasculitis due to direct invasion of the vessel walls.[24] Diagnosis of immune-mediated retinitis is often clinical, based on past history of a febrile illness (4 to 6 weeks prior). In our experience that patients had vitritis, multifocal retinitis, retinal vasculitis, choroidal neovascular membrane, neuroretinitis, retinal detachment and optic atrophy. All the patients were treated with a combination of oral ciprofloxacin and tapering dose of steroids. Visual outcome was poor in our patients with retinal detachment and optic atrophy. Management Treatment modalities described in the literature include topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, steroids in various forms including topical, subconjunctival, sub Tenon's, intravenous and oral steroids. Endophthalmitis secondary to typhoid was treated with intravitreal, topical and systemic antibiotic therapy. Parsplana vitrectomy was done in a patient with poor visual outcome and another patient ended up having evisceration following panophthalmitis. Post-treatment visual acuity in one series ranged between 6/60 to 6/12 in most of the cases and the fundus lesions almost resolved leaving retinal pigment epithelial changes and foveal thinning in cases with severe macular involvement.

Post Typhoid fever immune related reaction affecting the eye is a rare finding which can have various presentations in which typhoid retinopathy is not a well recognised sequelae.

Results

A 30-year-old male presented to our ophthalmology department in a Medical college in Andhra Pradesh with sudden, painless decreased vision for both distant and near in the left eye for 30 days associated with floaters. He gave a past history of typhoid fever 4 weeks prior to presentation.

Treatment and diagnostic details of the past typhoid fever were as follows: positive Widal test with significant titers for `O` antigen (1:320) and `H' antigen (1:40) while `AH' and `BH' antigens were non-reactive.

He began to experience decreased vision 4 weeks after the onset of treatment. On ophthalmic examination, her best corrected visual acuity was 6/36, N36 in the Left eye and 6/6, N6 in the right eye. There was no known history of Diabetes Mellitus or Hypertension. Anterior segment examination including slit lamp bio microscopy was unremarkable and IOP being within normal range for both eyes except for the presence of grade 2 RAPD in the Left eye.

Baseline investigations was done including complete Hemogram, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, Widal test, Venereal disease research laboratory tests (VDRL), Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ELISA, RA Factor, C-reactive protein, Random blood sugars, Mantoux test and Chest x ray. Other specific investigations like Dengue serology, peripheral smear for Malarial parasite; Antinuclear antibodies were ordered when required. Widal titres from previous records were assessed.

Diagnoses of Post Typhoid fever Retinitis (possibly immune-mediated) along with macular neurosensory detachment in Left eye were made.

In consultation with the patient and an internist, he was started on oral Ciprofloxacin 500mg (monotherapy)twice daily for 5 days along with Dorzolamide eye drops.

Patient was reviewed after 1 week. On fundus examination after 1 week, the lesions at the supero-temporal arcade and neurosensory detachment at the macula were still persistent. The patient was started on oral Prednisolone 1mg/kg body weight along with oral ciprofloxacin for another 5 days. The oral Prednisolone was tapered over a period of 1 month along with monitoring of systemic and ocular health.

Discussion

This study demonstrates resolution of immune-mediated retinitis following typhoid fever. The most likely etiology could be a viral etiology. Literature review reveals very minimal data related to typhoid fever causing retinitis.

In our study the patient presented with sudden, painless decreased vision for both distant and near in the left eye, with history of typhoid 4 weeks before the onset of ocular manifestations. He gave a past history of typhoid fever 4 weeks prior to presentation. Colemen W et al[14] in their study found that ocular onset was reported 6 weeks to 3 months later. Relhan N et al [5] found ocular manifestations occurred 6 weeks post typhoid fever.

Diagnosis of immune-mediated retinitis is often clinical, based on past history of a febrile illness (4 to 6 weeks prior) and is supplemented by laboratory workup. Retinitis-occurring post febrile illnesses have been reported after malaria, viral fevers, Chickungunya fever and also in non-infectious immune disorders (Behcet's disease, intraocular lymphoma). [25], [26] In our study by positive Widal test with significant titers for `O` antigen (1:320) and `H' antigen (1:40) while `AH' and `BH' antigens were non-reactive. In a study by Darton et al. culture-PCR assay performed well, identifying extra typhoid cases compared with routine blood culture alone.[19] A study done to compare PCR with blood culture, typhi‑dot and Widal test for the diagnosis of typhoid in patients taking antibiotics showed positivity rate of PCR was significantly higher as compared to blood culture, Typhi‑dot or Widal test for diagnosing typhoid in patients who were already taking antibiotics. [20] In a study by Acharya et al [22] they found high Widal titres were associated bilateral involvement, extensive lesions defined as disc involvement, retinitis, vasculitis and macular involvement and poor visual acuity which was found to be statistically significant.

Mild cases resolve without treatment, while severe cases may need a course of corticosteroids. In our study, he was started on oral ciprofloxacin 500mg (monotherapy) twice daily for 5 days along with dorzolamide eye drops. After 1 week, the patient was started on oral Prednisolone 1mg/kg body weight along with oral ciprofloxacin for another 5 days prednisolone was tapered over a period of 1 month along with monitoring of systemic and ocular health. According to studies by Mathur et al, Agarwal et al, Acharya P et al, the treatment modalities described for post viral retinitis are topical non steroidal anti inflammatory medications, steroids in various forms including topical, subconjunctival, sub Tenon’s, intravenous and oral steroids. [6], [7], [22]

Kujur S et al[23] in their study treated endophthalmitis secondary to typhoid with intravitreal, topical and systemic antibiotic therapy. Parsplana vitrectomy was done in a patient with poor visual outcome and another patient ended up having evisceration following panophthalmitis.

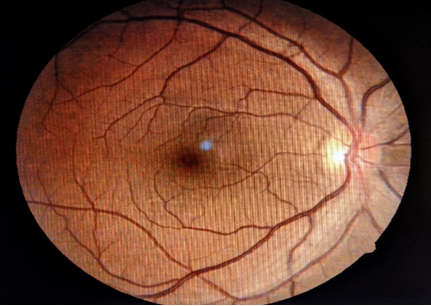

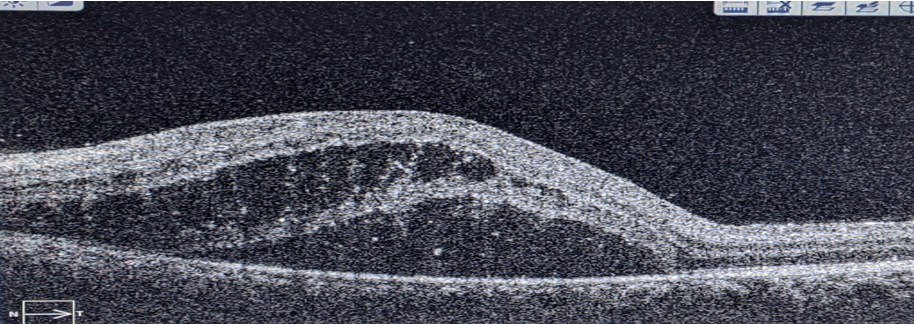

In our study, BCVA of left eye improved from 6/36 to 6/6(Figure 6). Left eye fundus, OCT and FFA were noted to be normal in comparison to a study Acharya P et al[22] who found in their study post‑treatment visual acuity in one series ranged between 6/60 to 6/12 in most of the cases and the fundus lesions almost resolved leaving retinal pigment epithelial changes and foveal thinning in cases with severe macular involvement.

Conclusion

Post-typhoid neuroretinitis evolves as a significant cause of visual morbidity. Younger age group and high Widal titres had a significant association with severity of the disease. Even though, spontaneous resolution is possible in mild cases, severe cases may need corticosteroids that help in improvement of symptoms and prevention of visual loss. Adjuvant therapy of steroid with topical antibiotics compared with monotherapy of oral antibiotics in a typhoid associated with Retinitis was found to be more effective and healing of lesions noted at a faster rate.

Conflicts of Interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Source of Funding

None.

References

- Duke-Elder S, Perkins ES. Diseases of the Uveal Tract. 9th Edn.. 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Schweintz GED. The ocular complications of typhoid fever, de Schweintz GE (eds.) Biblio Bazaar. . 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhushanker M, Topiwalla T, Ganesan G, Appandaraj S. Bilateral retinitis following typhoid fever. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Hughes EH, Dick AD. The pathology and pathogenesis of retinal vasculitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29(4):325-40. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Relhan N, Pathengay A, Albini T, Priya K, Jalali S, Flynn H. A case of vasculitis, retinitis and macular neurosensory detachment presenting post typhoid fever. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect . 2014;4(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Mathur JS, Nema HV, Char JN, Mehra KS. Post typhoid retinal detachment. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1970;18:135-7. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal M, Malathi J, Biswas J. Frosted branch angiitis in a patient with typhoid fever. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:776-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sen R, Saxena SN. Typhoid fever in Delhi area: An assessment based on bacteriological and some epidemiological findings. J Indian Med Assoc. 1968;50:297-304. [Google Scholar]

- Parry CM, Wijedoru L, Arjyal A, Baker S. The utility of diagnostic tests for enteric fever in endemic locations. Expert Rev Anti-infective Ther. 2011;9(6):711-25. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Hosoglu S, Wain J. The laboratory diagnosis of enteric fever. J Infect Dev Ctries . 2008;2(06):421-5. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- . World Health Organisation. Background document: The diagnosis, treatment and prevention of typhoid fever. Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Keddy K, Sooka A, Letsoalo M, Hoyland G, Chaignat CL, Morrissey A. Sensitivity and specificity of typhoid fever rapid antibody tests for laboratory diagnosis at two sub-Saharan African sites. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(9):640-7. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- WC. Short-duration typhoid fever. Am J Med Sci . 1909;137(6):781-9. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Coleman W, Buxton BH. The bacteriology of the blood in convalescence from typhoid fever. With a theory of the pathogenesis of the disease. J Med Res. 1909;21:83-93. [Google Scholar]

- Watson KC. Laboratory and clinical investigation of recovery of Salmonella typhi from blood. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:122-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye D, Palmieri M, Rocha H. Effect of Bile on the Action of Blood Against Salmonella. J Bacteriol. 1966;91(3):945-52. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Zhou L, Pollard A. A fast and highly sensitive blood culture PCR method for clinical detection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Zhou L, Pollard AJ. A novel method of selective removal of human DNA improves PCR sensitivity for detection of Salmonella Typhi in blood samples. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1). [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Darton T, Zhou L, Blohmke C, Jones C, Waddington C, Baker S. Blood culture-PCR to optimise typhoid fever diagnosis after controlled human infection identifies frequent asymptomatic cases and evidence of primary bacteraemia. J Infect. 2017;74(4):358-66. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Munir T, Lodhi M, Ali S, Zaidi SBH, Razak S, . Early diagnosis of typhoid by PCR For FliCd gene of salmonella typhi in patients taking antibiotics early diagnosis of typhoid. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:662-6. [Google Scholar]

- Redhuan N, Chin KL, Adnan AS, Ismail A, Balaram P, Phua KK. Salivary Anti-50kDa antibodies as a useful biomarker for diagnosis of typhoid fever. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-3. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya P, Ramamurthy LB, Venugopal KC, Manipur SR. Evaluation of posterior segment manifestations following typhoid fever-a clinical study. Indian J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;4:421-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kujur S, Ranga SN. Varied ocular complications of Enteric fever: A series of 9 cases. Int J Basic Appl Med Sci. 2016;6:86-8. [Google Scholar]

- Belizna CC, Hamidou MA, Levesque H, Guillevin L, Shoenfeld Y. Infection and vasculitis. Rheumatol. 2008;48(5):475-82. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Vishwanath S, Badami K, Sriprakash K, Sujatha B, Shashidhar S, Shilpa Y. Post-fever retinitis: a single center experience from south India. Int Ophthalmol . 2014;34(4):851-7. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- Balansard B, Bodaghi B, Cassoux N, Fardeau C, Romand S, Rozenberg F. Necrotising retinopathies simulating acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:96-101. [Google Scholar]

How to Cite This Article

Vancouver

N SS, E A, R UK, M N. A study on use of adjuvant therapy of steroid and antibiotics in treatment of unilateral retinitis following typhoid fever in a medical college in Kuppam [Internet]. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty. 2021 [cited 2025 Oct 28];7(1):89-93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2021.018

APA

N, S. S., E, A., R, U. K., M, N. (2021). A study on use of adjuvant therapy of steroid and antibiotics in treatment of unilateral retinitis following typhoid fever in a medical college in Kuppam. IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, 7(1), 89-93. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2021.018

MLA

N, Shiva Sagar, E, Ananthanag, R, Usha Kiran, M, Narayan. "A study on use of adjuvant therapy of steroid and antibiotics in treatment of unilateral retinitis following typhoid fever in a medical college in Kuppam." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty, vol. 7, no. 1, 2021, pp. 89-93. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2021.018

Chicago

N, S. S., E, A., R, U. K., M, N.. "A study on use of adjuvant therapy of steroid and antibiotics in treatment of unilateral retinitis following typhoid fever in a medical college in Kuppam." IP Int J Ocul Oncol Oculoplasty 7, no. 1 (2021): 89-93. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijooo.2021.018